Books as Symbols in Renaissance Art (BASIRA)

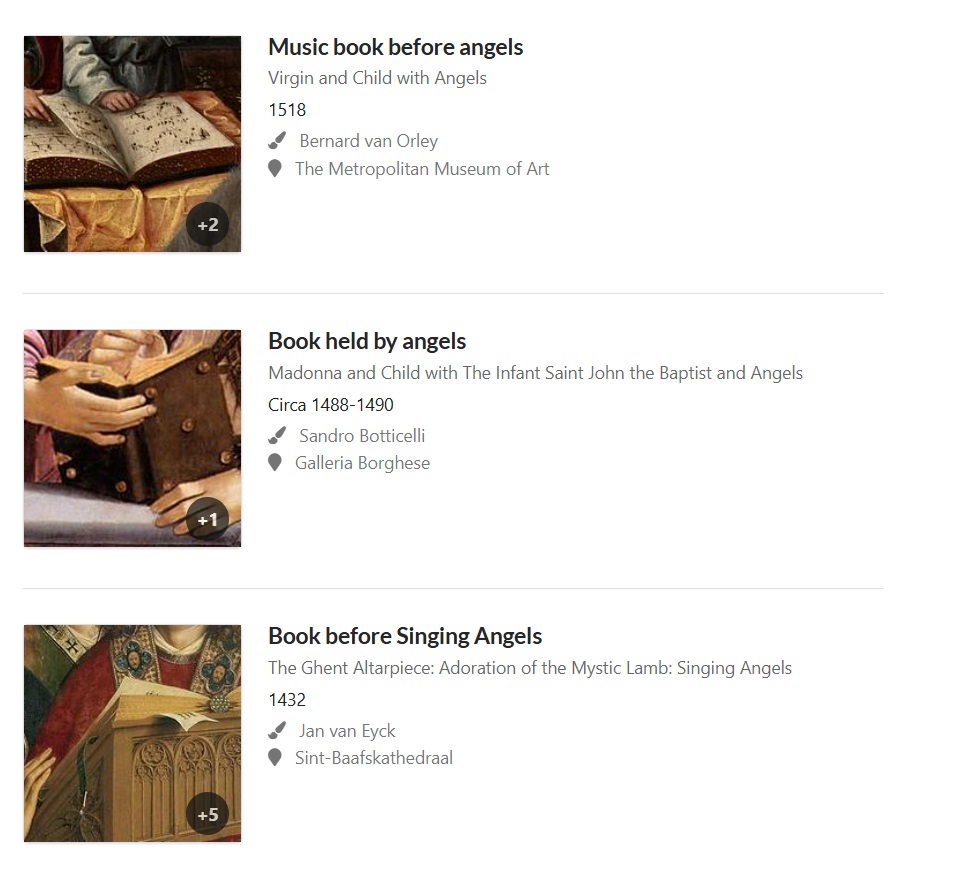

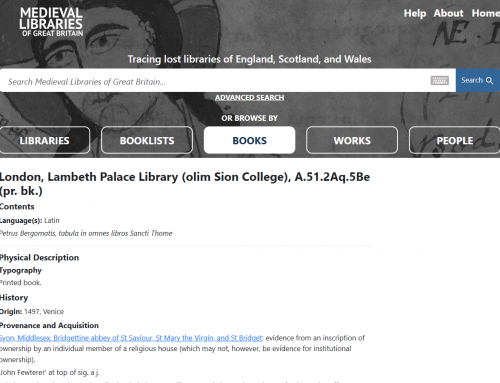

Visitors to museums, galleries, libraries and churches may have observed that books appear frequently in medieval and Renaissance art. Paintings, sculptures and stained glass provide insights into how books were used, but also how they were perceived. Depictions of books within books have traditionally received more attention than those in other media, but this growing database allows for cross media comparison, using sources from Europe, the Middle East, and north Africa.

Label on perfume sprinkler

The Books as Symbols in Renaissance Art (BASIRA) project aims to collect and make searchable images of books in a wide range of media from between about 1300 and 1600. Books are defined extremely broadly, encompassing medieval manuscripts and early printed volumes, but also scrolls, single sheets, tablets and even a label on a perfume sprinkler. At the moment the database contains over 3,000 entries, but it has the potential expand enormously, and users are encouraged to submit photographs they have taken of additional examples.

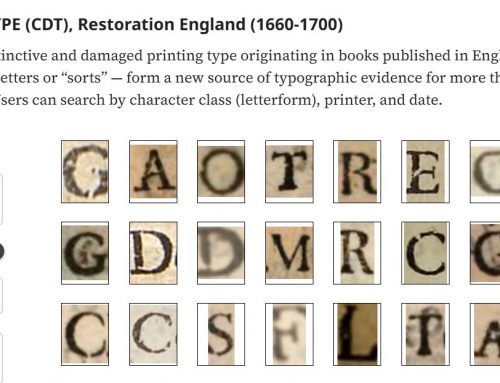

Each entry in the database has an image, together with detailed metadata designed to create a precise description of the structure and content of the depicted book, as well as its relationship to representations of people and other objects. This allows users to browse the dataset not only by familiar categories such as date, place, and material, but also by binding type, orientation of the book within the image, number of text columns, or the presence of bookmarks. This may prove particularly useful for the history of pre-modern bindings, many of which have not survived.

The depicted books range from sketches only a few millimetres in size to detailed depictions of identifiable texts. The database enables researchers to begin to pose a remarkable range of questions about attitudes towards books in the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance. These include, what did angels read? How did the books read by the Virgin at the Annunciation change over time? And which depicted books survive today?

At the moment, works in collections in the United States dominate the dataset, but this will no doubt change if more researchers from other parts of the world begin to contribute examples. This is already a database that a user can browse happily for hours, but it has the potential to grow into an extremely valuable resource for art historians and those interested in the history of the book.

Laura Cleaver, Member of Council