December 2021

12 Days of Bibliographical Video Delights

One of the benefits of the past 18 months has been the fluidity in which libraries, archives, museums and galleries have migrated their public events and talks to an online environment, and the recordings made freely available for those who wish to re-watch, catch-up, or even assign them as part of a class. Making decent-quality videos for YouTube and other streaming services has become easier and cheaper, and a number of new professionals have brought digital-native skills to the bibliographical world which has enhanced the reach of those interested in bibliographic pursuits. Videos add a new dimension for understanding books in an online environment – they show the book in context in scale to an environment or to a person, they show an object’s three-dimensionality, and they offer new ways of explaining historical or mechanical context. For my Council’s Choice, then, I’m offering a “12 Days of Bibliographical Video Delights” for the festive season:

- Day 1: Timeline finally released the 2008 The Machine that Made Us on YouTube a few years ago – watch the full length documentary of Stephen Fry bouncing around Europe trying to get to grips with Gutenberg and printing history;

- Day 2: Brady Haran’s Objectivity channel on YouTube has seen a fantastic partnership develop between a brilliant and curious presenter/vlogger and cultural heritage collections. A personal favourite is Newton’s Dog-Ears;

- Day 3: Cornelius Berthold (Hamburg)’s short film on miniature Qur’ans, 39 Grams of Qur’an, communicates to the viewer the size and design of this beautiful tradition;

- Day 4: The British Museum’s ‘Curator’s Corner’ vlogs are full of excellent content, some favourites include: Francesca Hillier (BM Archivist) talking about giraffes and Irving Finkel on the cuneiform collections; also from the BM, the size and scale Dürer’s Triumphal Arch is on display in this magnificent video from the conservation department;

- Day 5: Linda Hall Library released a short series this year from curators Jason Dean and Jamie Cumby, Paper Cut, and their episode on first acquisitions is a delight;

- Day 6: See some remarkable collections and conservation at Harvard Law School Library’s video on their medieval manuscripts;

- Day 7: The Brain Scoop’s visit to the Field Museum’s Mary W. Runnells Rare Book Room is a joy for anyone interested in history of science;

- Day 8: The British Library’s ‘Curators on Camera’ series offers great snippets into collections, especially those featured in recent exhibitions, including Emma Harrison on the Double Pigeon Chinese Typewriter, and Andrea Clarke on Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks; and Adrian Edwards’s tour of the King’s Library Tower offers a unique chance to go inside an iconic space.

- Day 9: Another opportunity to get inside a very special library is the Inside the Fellows’ Library from Winchester College;

- Day 10: Although not strictly speaking a video about books, the National Library of Scotland’s Doors Open Day 2021 – The Void takes us to a rarely-seen liminal space between the NLS and George IV Bridge;

- Day 11: Allie Alvis’s Book Historia channel has brought bibliography to new audiences, my favourite being ‘Heavy Metal Bookbinding!’;

- Day 12: Giovanni Varelli’s Singing the Collections explores the recreation of medieval polyphony found in fragments of manuscripts found in book bindings;

Finally, in case you weren’t already aware, The Bibliographical Society has recently started hosting its recorded lectures on the School of Advanced Study’s YouTube channel – including a chance to revisit our Virtual Summer Visit to the State Library of Victoria.

Daryl Green, Council Member

September 2021

Five hundred years of Plantin

Christophe Plantin was born near the French town of Tours, probably around 1520. After working in Caen and Paris he moved to Antwerp, then one of the most important commercial cities in Europe, where he established a publishing house that was to last for three centuries. The enduring fame of the press rests on the nearly 2,450 editions published in Plantin’s lifetime – scholarly editions of classical authors, scientific works and erudite works of Biblical scholarship, as well as popular religious and secular titles. However, the extraordinary wealth of the surviving archives offers us much more, providing an unparalleled resource for many aspects of book trade history from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The focus of my own research in the archives are the accounts which cover the sale and distribution of Plantin’s publishing output across Europe (as well as books resold from other publishers). These record sales to other members of the trade in many different countries, individuals who visited Antwerp or lived more locally, and institutions such as monasteries and Jesuit colleges. Most of the accounts for this period have been digitised and are now available online. A PDF version of Jan Denucé’s inventory acts as a finding aid to the online collection.

Over the last decade the Museum has made significant progress in increasing access to the collections online. Another recent project has been the digitisaton of 14,000 woodblocks. They have now partnered with the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library in Antwerp and Google to digitise a large portion of their book collections.

In a separate project, the majority of Plantin’s surviving correspondence is now available online. There are copies of over 1,500 letters sent by Plantin, contained in four letterbooks. These were edited, and supplemented with incoming letters and others held elsewhere, by Max Rooses and Jan Denucé in nine volumes published from 1883 to 1918. These volumes of edited letters have been digitised and are available on the Internet Archive. An online catalogue, linked to the digitised volumes, has been created by Early Modern Letters Online at Oxford. In addition, the original letterbooks (for outgoing letters) have also been digitised.

As part of the celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Plantin’s birth the Museum mounted two exhibitions featuring documents from the archives – ‘Letters from Plantin’ and ‘Traveling with Plantin’. Most of us did not have the opportunity to see these exhibitions in person but you can still visit the Museum virtually.

Julianne Simpson, member of Council

August 2021

La Bibliothèque des Amis de l’Instruction, Paris

Among the many libraries of the City of Paris is the Bibliothèque des Amis de l’Instruction, in the rue Turenne in the third arrondissement. Housed by the City, it began in 1861 very much outside official structures. One of the leading persons behind its creation was Jean-Baptiste Girard, a lithographer, not a shop owner but a worker. Unemployed from 1848 he moved in circles which were increasingly seen as dangerous in the newly restored Empire, supporting, for instance, an organisation led by the radical feminist Jeanne Deroin, washer woman and teacher. It would seem that his first real encounter with a library was in 1850–1851 when he was jailed for 22 months for being the secretary of a union of workers’ mutual organisations.

The library was led by a group of manual workers, and its constitution demanded that 50% of the governing body should be workers. The library differed from other publicly accessible libraries in important ways. Members were co-owners of the library collections, decided on rules and regulations, elected the director of the library, and decided on what was acquired for the library. They could borrow the books to take home to read in their few free hours. Unusually for France at the time, women had full access to the library.

This was evidently too radical and in 1863 the mayor of the arrondissement demanded control. When this was refused, he declared it anarchist and gave it 12 hours to leave its rooms. The library began a period of migration, but it could not maintain its full independence. By collaborating, its director ensured its survival but abandoned its radical nature, declaring that popular libraries were wonderful but that they needed strict control. About half the members left, and Girard moved on to help form associative libraries elsewhere. In 1867 a new director began gently steering the library in its original direction again. It moved to its present building in 1884 and into its present rooms in 1918, which are largely unchanged since then. The move and the associated building work was coordinated by one of the longest serving leaders of the Bibliothèque des Amis, Pauline Weiler (deported to Auschwitz in 1944).

Most of the 1862 collection is still there among the some 15,000 volumes, and can be examined in the evocative library rooms. The 1862 catalogue survives and is available on-line. The fascinating first register of members records the addresses and professions of the members and jointly with the books give a detailed insight into the reading of working class people in Paris, for instruction and for pleasure. Some of the editions in the collection can be explored on-line; publicly accessible digital copies having been identified on the Bibliothèque virtuelle 1862.

A very active group of volunteers organises lectures on topics germane to the institution and its history. Many are available on line, for instance the talk by Michel Blanc, Amis de l’instruction : émancipez-vous, lisez !, which gives an introduction to the library, its history and its collection. If you would rather read than listen there is an on-line version of Lectures et lecteurs au XIXe siles : La Bibliothèque des Amis de l’Instruction. Aces du Colloque tenu le 10 novembre 1984 (Paris : Bibliothèque des Amis de l’Instruction, 1985).

Kristian Jensen, Past President

July 2021

A bibliophile’s dream: C. G. Jung’s alchemical library

Much as the eyes are said to serve as windows into the soul, so the library may be considered the door to a person’s mind. This is perhaps especially true of the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. At the time of his death in 1961, Jung had accumulated a library of some 5,000 titles related to his work in psychiatry, among them a sizeable number of rare, early printed works on alchemy. Readers of the following lines will understand why, as a fellow-bibliophile, I find this alchemical core of Jung’s library utterly compelling. It appears that the idea of forming a library of rare alchemica had come to Jung in his dreams in the mid-1920s, i.e. roughly a decade before his intense engagement with the subject started. In retrospection he wrote:

Before I discovered alchemy, I had a series of dreams which repeatedly dealt with the same theme. Beside my house stood another, that is to say, another wing or annex, which was strange to me. Each time I would wonder in my dream why I did not know this house, although it had apparently always been there. Finally came a dream in which I reached the other wing. I discovered there a wonderful library, dating largely from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Large, fat folio volumes, bound in pigskin, stood along the walls. Among them were a number of books embellished with copper engravings of a strange character, and illustrations containing curious symbols such as I had never seen before. At the time I did not know to what they referred; only much later did I recognize them as alchemical symbols. In the dream I was conscious only of the fascination exerted by them and by the entire library. It was a collection of medieval incunabula and sixteenth-century prints.

And form this library he did. In a concerted collecting effort primarily concentrated on the years between 1935 and 1940, Jung acquired nearly three hundred rare works on alchemy, magic, and kabbalah dating from before 1800. Thanks to the Stiftung der Werke von C. G. Jung, these rare books are available fully digitised online at e-rara, and can be read on a couch of one’s own. The virtual visitor to Jung’s library will also enjoy the website of the Haus C.G. Jung, which, among other things, contains historic photographs of Jung’s library at his home in Küsnacht, Switzerland, where he lived – and collected books – for more than half a century.

Further information on the Stiftung der Werke von C. G. Jung is available on their website, which also hosts the informative and interesting article on the history of Jung’s alchemical collection from which the quotation above is taken: Thomas Fischer, ‘The Alchemical Rare Book Collection of C. G. Jung’, International Journal of Jungian Studies 3:2, 169-180, esp. p. 171, quoting from Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York, 1963), p. 202.

Anke Timmermann, member of Council

June 2021

International Kelmscott Press Day

To mark the 125th anniversary of the publication of William Morris’s edition of the works of Chaucer, 26th June has been designated ‘International Kelmscott Press Day’ by the USA’s William Morris Society. Although many people know Morris primarily through his furniture, stained glass and wallpaper, he turned at the end of his life to books, producing over fifty books at his press, named after his Tudor house on the Thames. Increasing mechanization during the nineteenth century saw books produced more quickly under industrial conditions, the results lacking some of the handmade beauty of those of earlier centuries. The purpose of his ‘typographical adventure’, as he called it, was to bring beauty back to the world of book production. As a collector of early printed books and medieval manuscripts (including a thirteenth-century psalter now at Cambridge University Library), Morris was influenced by the great attention paid by their creators to lettering, type design, imagery and binding. He spoke of these concerns in a paper given to The Bibliographical Society in 1893 (entitled The Ideal Book), where he noted that ‘ornament must form as much a part of the page as the type itself, or it will miss its mark’.

By way of marking International Kelmscott Press Day, I wanted to highlight (in a blog, accessible here) some items relating to Morris in the collections of Cambridge University Library, where I work. These include examples of books from the Press (notably proofs annotated by Morris of his edition of Beowulf, fully digitised online) and some of Morris’s typographical equipment (including punches for his type and one of his paper moulds) from our Historical Printing Room.

Liam Sims, member of Council

May 2021

Globes in print and online

Returning to work at the end of 2020 having being furloughed for most of the year was an unusual experience. Along with many colleagues, the following months have meant homeworking. It has been a liberating experience to be able to read more widely and delve into different areas of our collections. Apart from the 1592 Molyneux globe at Petworth, the rest have received little attention over the decades. Regarded as not quite library material, nor furniture, they have fallen between specialisms until recently. In the future, globes and maps will be receiving more curatorial attention. One of my go to books at the moment is Elly Dekker’s Globes at Greenwich: a catalogue of the globes and armillary spheres in the National Maritime Museum (1999). It is packed with introductory articles about globes, their care and construction, as well as being a detailed catalogue of the museum’s holdings. Some of the detail has been added to the online globe catalogue on the NMM’s website, but not all, so Dekker’s book is a useful supplement to have to hand.

Although digital mapping has enabled much closer inspection of the earth’s surface from your own desktop, people are still fascinated by old globes. Often regarded as an integral part of furnishing a library, many have passed from their original homes into institutional collections. Over the last year or so, more content has become available online. The British Library has begun 3-D digital photography of its collections, which you can whizz round and zoom in to look closer at the details if you are on a touchscreen device: https://www.bl.uk/collection-guides/globes#. Many local and national collections are putting their globes online. One of the biggest collections is on display at the Austrian National Library, where you can also view the Gold Cabinet: https://www.onb.ac.at/en/museums/globe-museum/. For those who want more detail, online auction catalogues are handy for those whose first instinct is to search by mobile phone. The catalogue entries then often lead to the scholarly works on which they are based, such as those of Peter van der Krogt, Elly Dekker, Sylvia Sumira and many others. In the UK we deal mainly with European globes, produced from the exploration voyages of European explorers. Islamic and Eastern globes rarely feature in Western collections, yet they are fundamental to our understanding of the mapping of the earth and heavens.

Yvonne Lewis, member of Council

April 2021

The UK Reading Experience Database

Some years ago, I stumbled across UK RED, the UK Reading Experience Database (http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/index.php), and have returned to it many times since when investigating a particular book, to see what real people at the time perhaps thought of it, but often just out of idle curiosity when thinking about an author.

Take, for example, Dostoevky. There are infamous appraisals of the Russian novelist which one often comes across in the literature, such as that of D. H. Lawrence (‘a rat, slithering along in hate’), or Robert Louis Stevenson saying that reading Crime and Punishment was ‘like having an illness.’ But what of others? Pleasingly, UK RED gives a range. We learn that Crime and Punishment (in French) was one of the books Virginia Woolf read on her honeymoon in 1912: ‘You can’t think with what a fury we fall on printed matter, so long denied us by our own writing! I read 3 new novels in two days: Leonard waltzed through the Old Wives Tale like a kitten after its tail: after this giddy career I have now run full tilt into Crime et Chatiment, fifty pages before tea, and I see there are only 800; so I shall be through in no time. It is directly obvious that he [Dostoevsky] is the greatest writer ever born.’ (There had been an English version, published by Vizetelly in 1886, but Constance Garnett’s important translation did not appear until 1914.)

At the other end of the social spectrum, we find Jack Jones, a labourer from the mining town of Blaengaerw, who used to borrow Russian literature from Cardiff Central Library once a month: ‘he would exchange twelve to twenty books and take them home in an old suitcase. He read Tolstoy and Gorky, and raced through most of Dostoevsky in a month. He was guided by a librarian who, like a university tutor, demanded an intelligent critique of everything he read.’

Simon Beattie, member of Council

March 2021

The digitisation of incunabula at the British Library

|

I’ve chosen to write about something that’s very important to me and that’s made a difference to incunabula researchers around the world during lockdown. When I took on the role as Lead Curator, Incunabula and Sixteenth Century Printed Books, at the British Library a few years ago, starting a project to digitise the Library’s collection of incunabula was high up on my agenda. It was finally begun with the inclusion of the English and unique incunabula in the Library’s corporate Heritage Made Digital programme. While the full colour cover-to-cover digitisation of all the Library’s copies of English incunabula was an obvious choice and a high priority, it has of course been the inclusion of the unique items that has proved particularly valuable for researchers, especially while we are all dependent on material being accessible in digital form. |

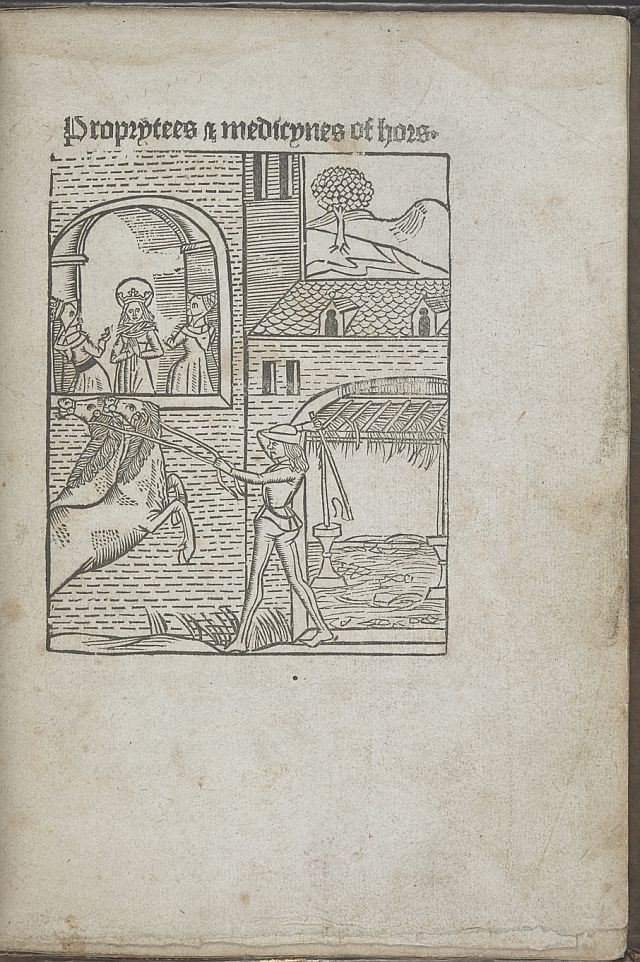

Propertees and medicynes of hors, Westminster, Wynkyn de Worde, [about 1497-98], ISTC ip01019200. © British Library Board, IA.55279., a1r. |

|

With most of the digitisation of the English and unique incunabula complete before we went into the first lockdown in March 2020, I worked closely with my colleagues in Heritage Made Digital throughout last year to make the high-resolution images freely available through Explore the British Library. We’ve also so far added over 400 links to the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC) which can be found by searching for ‘Electronic facsimile : British Library, London’. The images can also be accessed via links in records in the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW). The images of a number of volumes are still waiting to be ingested, but they will become accessible over the next few months. While this work will continue until all English and unique incunabula in the British Library are freely available to a worldwide audience, we are now planning for the digitisation of further sections of one of the world’s largest collections of incunabula. Karen Limper-Herz, Hon. Secretary and Vice-President |

|

February 2021

The Takamiya Collection at Yale

One of the greatest book collecting achievements of the past fifty years are the medieval manuscripts assembled by Toshiyuki Takamiya, Professor Emeritus of Keio University in Tokyo. The focus is on English books and book production, and at the heart of the collection are the fifty-one Middle English manuscripts including the classics of English poetry (three important manuscripts of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Gower’s Confessio Amantis, Lydgate’s Fall of Princes), works of spiritual devotion in prose and verse, historical chronicles in roll and codex form, two Wycliffite Bibles plus a fragment, scientific and medical texts, a fine copy in its original binding of Mandeville’s Travels, and so forth. The Latin and other manuscripts are hardly less distinguished further demonstrating the collector’s interest in English history and literature, heraldry, Arthurian and other romances, book production and the history of script, book collecting, and English medieval provenances.

The collection was acquired by the Beinecke Library at Yale and each manuscript is identified by its special Takamiya shelf-mark. There was a major exhibition in 2017, and the contents can be viewed online: Making the Medieval English Manuscript: The Takamiya Collection at the Beinecke Library.

https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/exhibitions-visiting/special-exhibitions/making-medieval-english-manuscript-takamiya-collection

Richard Linenthal, Vice-President

January 2021

Last year marked the fortieth anniversary of the publication of the first volume (in two parts) of Peter Beal’s Index of English Literary Manuscripts, 1450–1625. A second volume was published, again in two parts (1987 and 1993), covering the period 1625 to 1700. Twenty years after the publication of the last part, with funding from the AHRC, the Index became an open-access, online database, the Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts, 1450–1700 (CELM: https://celm-ms.org.uk/). The Catalogue is not just a searchable version of the Index, but a hugely expanded revision of it. The 123 authors covered in the Index became 237; the number of individual manuscript entries grew from about 23,000 entries to 37,000. All the Index entries and the author introductions were revised, and among the many new entries were 75 concerning women writers. CELM’s contents can be viewed either by authors or by repositories.

Scholars of the period, especially historians of the book, are exceptionally well served by such familiar resources as the Short-Title Catalogue and ESTC, EEBO and ECCO, the OED and ODNB, Electronic Enlightenment and Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. The wealth of material in CELM about authors and their writings, their manuscripts, letters, documents, the books they owned, as well as the history of who collected these items is extraordinary. Such a comprehensive, scholarly, wide-ranging, and accurate catalogue exists for no other period of English literature or for the literature of any other country. It is all the more astonishing that it should be the work of one man. A day spent without looking up something in CELM or reading part of it is often a wasted day.

H. R. Woudhuysen, Past President